by Bronston McCord | Jan 10, 2018 | General

Ennis Britton is very pleased to announce that Ryan M. LaFlamme, Pamela A. Leist, Giselle S. Spencer, Erin Wessendorf-Wortman, and Megan Bair Zidian have been promoted to the position of shareholder in the firm.

“We are proud to have such a fine cohort of attorneys who have a genuine passion for education law,” said C. Bronston McCord, managing shareholder of Ennis Britton. “Their selection to this position is a testament not only to their exceptional abilities as attorneys but also to the continued success of the firm and its commitment to excellence.”

Ryan M. LaFlamme served as a law clerk for the firm during law school before joining the firm as an attorney. He is a member of the firm’s Construction and Real Estate, School Finance, and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and practices in many areas of the law concerning school districts including employment issues, construction, student discipline, workers’ compensation, labor arbitration, staff discipline, and policy review and drafting, in addition to general school law and local government practice. Ryan also serves as assistant prosecutor for two municipalities in Ohio. He has represented school district boards of education in both state and federal court. He has also defended school boards before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the state and federal Offices for Civil Rights, the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation Review Commission, and the Unemployment Review Commission.

Ryan M. LaFlamme served as a law clerk for the firm during law school before joining the firm as an attorney. He is a member of the firm’s Construction and Real Estate, School Finance, and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and practices in many areas of the law concerning school districts including employment issues, construction, student discipline, workers’ compensation, labor arbitration, staff discipline, and policy review and drafting, in addition to general school law and local government practice. Ryan also serves as assistant prosecutor for two municipalities in Ohio. He has represented school district boards of education in both state and federal court. He has also defended school boards before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the state and federal Offices for Civil Rights, the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation Review Commission, and the Unemployment Review Commission.

Ryan frequently speaks throughout Ohio on education-related topics. He volunteers as a high school mock trial coach annually. He also served as a trustee for the Citizens for the North College Hill Community Center and has served as a treasurer on several levy campaigns. Ryan earned his J.D. from Northern Kentucky University in 2008 and is licensed to practice law in Ohio and in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Pamela A. Leist served as a law clerk for the firm before joining the firm as an attorney. She is a member of the Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and assists clients with a variety of education law issues including special education, student discipline, labor and employment law, negotiations, board policy review and development, and legislative review. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. She also serves as the firm’s marketing coordinator.

Pamela A. Leist served as a law clerk for the firm before joining the firm as an attorney. She is a member of the Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and assists clients with a variety of education law issues including special education, student discipline, labor and employment law, negotiations, board policy review and development, and legislative review. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. She also serves as the firm’s marketing coordinator.

Pam frequently presents across the state of Ohio on issues related to school law and operations. She has served the local community in many capacities including director of marketing for the Cincinnati Memorial Hall Centennial Event Planning Committee, member of the board of trustees for the North College Hill Community Seniors, Executive Committee member for the North College Hill Business Association, and planning chair for the Ohio State Bar Association’s School Law Workshop. She is also a member of the Ohio State Bar Association’s Leadership Academy Class of 2016. She is currently a legal advisor for the Cincinnati Bar Association High School Mock Trial Competition. Pam earned her J.D. from the University of Cincinnati in 2007.

Giselle S. Spencer is a member of the firm’s Special Education, Workers’ Compensation, and Finance Practice Teams. She counsels school district boards of education and administration on many aspects of education law including employment matters, workers’ compensation, property valuation, student discipline, public records, special education, discrimination complaints, and board governance. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, county Boards of Revision, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Industrial Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. Prior to entering private practice, Giselle served as director of legal services for Dayton Public Schools and chief legal counsel for Columbus Public Schools. She has also served as chief examiner for the Dayton Civil Service Commission.

Giselle S. Spencer is a member of the firm’s Special Education, Workers’ Compensation, and Finance Practice Teams. She counsels school district boards of education and administration on many aspects of education law including employment matters, workers’ compensation, property valuation, student discipline, public records, special education, discrimination complaints, and board governance. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, county Boards of Revision, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Industrial Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. Prior to entering private practice, Giselle served as director of legal services for Dayton Public Schools and chief legal counsel for Columbus Public Schools. She has also served as chief examiner for the Dayton Civil Service Commission.

Giselle frequently presents on various education law topics at the state and national levels and is a featured presenter for several school employee associations throughout Ohio. Giselle is a 2011 recipient of President Barack Obama’s Volunteer Service Award and has an extensive history of volunteer service, including as a board member for the Habitat for Humanity in Dayton and in Greater Cleveland and as past president of the Thurgood Marshall Law Society. She is a former adjunct professor at Capital Law School and current member of the National School Boards Association Council of School Attorneys, the Norman S. Minor Bar Association, and other bar associations. Giselle earned her J.D. from Ohio Northern University in 1986.

Erin Wessendorf-Wortman advises clients on a variety of education law matters including labor and employment issues, student discipline and rights, special education, relationships with school resource officers, serving transgender students, employee misconduct and investigations, and general school law practice. She is also a member of the firm’s Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams. Erin has represented school boards before a variety of federal and state administrative agencies including the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, State Employment Relations Board, Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.

Erin Wessendorf-Wortman advises clients on a variety of education law matters including labor and employment issues, student discipline and rights, special education, relationships with school resource officers, serving transgender students, employee misconduct and investigations, and general school law practice. She is also a member of the firm’s Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams. Erin has represented school boards before a variety of federal and state administrative agencies including the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, State Employment Relations Board, Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.

Erin is a frequent presenter at professional conferences and at administrator and staff in-service trainings. She is a member of the Cincinnati Bar Association and the Ohio State Bar Association. Erin earned her J.D. from The Ohio State University in 2009.

Megan Bair Zidian advises public school districts and boards of education on a variety of education law matters including collective bargaining, labor and employment issues, student discipline and privacy issues, special education and board policy, and administrative guideline development. She is a member of the firm’s Special Education and School Finance Practice Teams. She has defended boards of education in arbitration, special education due process hearings, and state and federal administrative agencies including the State Employment Relations Board, Ohio Civil Rights Commission, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Office for Civil Rights. Megan also has extensive experience in the school transformation process and assists academically distressed districts in navigating that progression.

Megan Bair Zidian advises public school districts and boards of education on a variety of education law matters including collective bargaining, labor and employment issues, student discipline and privacy issues, special education and board policy, and administrative guideline development. She is a member of the firm’s Special Education and School Finance Practice Teams. She has defended boards of education in arbitration, special education due process hearings, and state and federal administrative agencies including the State Employment Relations Board, Ohio Civil Rights Commission, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Office for Civil Rights. Megan also has extensive experience in the school transformation process and assists academically distressed districts in navigating that progression.

Megan is a frequent speaker at school conferences and regularly provides in-service training to school administrators and staff members. She serves on the Council of School Board Attorneys for the Ohio School Boards Association and is a member of the Council of School Attorneys of the National School Boards Association. Megan earned her J.D. from the University of Akron in 2011.

Please join us in congratulating each of them on their new role at Ennis Britton!

by Bronston McCord | Dec 6, 2017 | General

We are very pleased to announce that four Ennis Britton attorneys have been selected as 2018 Ohio Rising Stars! No more than 2.5 percent of attorneys in Ohio receive this award, which is given for demonstrating excellence in the practice of law. Congratulations to these Ennis Britton attorneys!

Super Lawyers is a national rating service that publishes a list of attorneys from more than 70 practice areas who have attained a high degree of peer recognition and professional achievement.

To qualify as a Rising Star, an attorney must score in the top 93rd percentile during a multiphase selection process that includes peer review and independent evaluations. A Super Lawyers rating is considered a very prestigious designation in the legal field, and we commend Pamela, Gary, Erin, and Megan for their continued achievement!

Pamela Leist is an attorney who has been with Ennis Britton since 2005, when she began serving as a law clerk while attending law school. As a member of Ennis Britton’s Special Education Team and Workers’ Compensation Team, she represents school districts across Ohio on a number of issues including special education, student discipline, labor and employment matters, and more. She also serves as the firm’s marketing coordinator. Pam is a frequent presenter on many education-related topics.

Gary Stedronsky is a shareholder who has been with Ennis Britton since 2003. He started as a law clerk while attending law school. As a member of Ennis Britton’s Construction and Real Estate Team and School Finance Team, he provides counsel to school districts throughout Ohio on matters related to property issues, public finance, tax incentives, and more. He is a published author and frequent presenter on many education-related topics. This is Gary’s fifth year in a row to receive this prestigious award.

Erin Wessendorf-Wortman is an Ennis Britton attorney. As a member of Ennis Britton’s Workers’ Compensation Team and Special Education Team, Erin represents school districts across Ohio on a variety of matters including labor and employment issues, civil rights, special education, public records, and more. She is a published author and frequent presenter on many education-related topics. This is Erin’s second year in a row as a Rising Star.

Megan Bair Zidian is an Ennis Britton attorney who advises school districts on a variety of education law matters. As a member of Ennis Britton’s Special Education Team and School Finance Team, Megan represents boards of education on collective bargaining, student discipline, board policy, and much more. She is a frequent speaker at school conferences and in-service trainings for staff and administrators. This is Megan’s second year in a row to receive the Rising Star award.

Visit the Super Lawyers website to learn more.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | May 23, 2017 | General, Student Education and Discipline

In a unanimous opinion, the Ohio Supreme Court has held that a school’s search of an unattended bag, and the two subsequent searches that initiated from the initial search, were constitutional. The court held that the searches served a compelling governmental interest in protecting the safety of the students. Two lower courts had ruled that the subsequent searches were unconstitutional and thus suppressed the evidence found in those searches – including ammunition and a gun.

Whetstone High School student James Polk left a book bag on his school bus. The bus driver found the book bag and gave it to the safety and security resource coordinator, Robert Lindsey, who checks the buses to ensure that no students are remaining on board. Lindsey was not a police officer. Based on the high school’s practice of searching unattended book bags to identify the owner and to ensure the contents are not dangerous, Lindsey opened the bag and saw some papers and notebooks, along with Polk’s name written on one of the papers (search 1). He had heard that Polk was possibly in a gang, so he took the bag immediately to the principal’s office, where together they conducted a complete search of the book bag (search 2).

In conducting search 2, the principal and Lindsey found bullets in the book bag and then contacted a police officer. When the police officer arrived, they found Polk and searched him and the book bag he was carrying (search 3). They found a handgun in the book bag during search 3.

On trial for conveyance or possession of a deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance in a school-safety zone, Polk asked the court to suppress the evidence – both the bullets and the handgun – arguing that the searches were unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment, which protects from unreasonable searches and seizures. Both the trial court and the court of appeals granted his motion to suppress the evidence, holding that search 1 – Lindsey’s initial opening of the bag enough to see Polk’s name on a document – was the only legitimate search. The other two searches, the courts held, were unconstitutional.

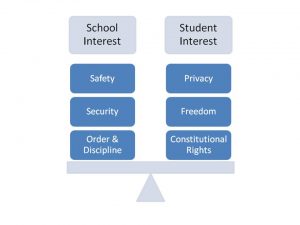

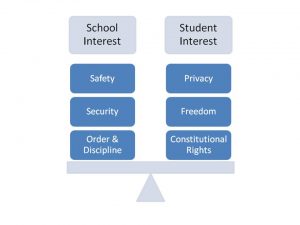

In general, under the Fourth Amendment, a police officer must have probable cause and a search warrant to conduct a search. However, courts have held that school searches may be conducted under a lesser standard of reasonable suspicion: justified at inception and reasonable in scope. In this case, the Ohio Supreme Court was tasked with determining whether the search protocol used was reasonable through balancing the government’s interest in safety and security against the student’s privacy interests.

The court centered on the constitutionality of search 2: whether it was permissible for the principal and Lindsey to conduct a full search of the student’s bag, when search 1 provided them with the identity of the owner of the unattended book bag.

In its finding, the court determined that it was appropriate for Whetstone High School to conduct complete searches of unattended book bags to ensure that they do not contain dangerous contents. Anything less than a complete search would not be enough to ensure safety and security for students. Key to this determination was that Whetstone High School required searches of unattended book bags to not only identify the owners but also to verify that the contents of the book bag are not dangerous. This was their protocol, albeit unwritten. Further, the search protocol was appropriate, reasonable, and reflective of the school’s obligation to keep students safe in a time when schools face a myriad of security concerns (e.g., school shootings, bomb threats, terrorist attacks). As a result, search 1 was inadequate in the court’s mind as it did not advance the school’s interest in ensuring safety and security of its students. Search 2 was required to fulfill this interest.

Additionally, the court found that the student’s expectation of privacy in his unattended book bag was “greatly diminished.” A person’s reasonable expectation of privacy diminishes when an item is lost or unattended, to the extent that the contents may be examined by the person who has found the item. Furthermore, a lost item in a closed container such as a book bag would carry an even lesser expectation of privacy, especially in a school setting, which must ensure the safety and security of all students.

Therefore, in balancing the school’s strong interest in protecting its students against Polk’s low expectation of privacy in the unattended book bag, the court determined that search 2 was reasonable and appropriate because the school needed to not only identify the owner of the book bag but also ensure the contents of the book bag were not dangerous. The court did not comment on search 3 but instead left the resulting judgment on that search to the lower court to make, consistent with this new decision.

State v. Polk, Slip Opinion No. 2017-Ohio-2735.

by Ryan LaFlamme | Apr 5, 2017 | General, Legislation

General Assembly Once Again Changes Rules on Disposal of Real Property

In 2015 Ohio’s General Assembly enacted R.C. 3313.413. This statute added another step to the process for disposing of real property worth $10,000 or more. The statute required school districts to first offer the property to “high-performing” community schools, as designated by the Ohio Department of Education. These schools may be located anywhere in the state of Ohio. Then, assuming no such high-performing school took up the offer, the district was required to offer the property to any start-up community school as well as any college-preparatory boarding school located within the district’s territory.

The designated list of high-performing community schools initially published by ODE contained 22 schools, so any district with an interest in selling a piece of real estate it owned was required to issue 22 offer letters, one to each these schools. Just as with the offer to community schools within a district’s territory, the offer to the high-performing schools could be for no more than the appraised value (the appraisal not being more than a year old) and the offer had to remain open for 60 days.

These relatively new requirements have now been modified by House Bill 438, which was signed in January and becomes effective on April 6. Under the new law, districts are back to the previous system of only having to offer properties to community schools and college-preparatory boarding schools within their territory – including high-performing community schools.

Along with the change in territory is a change in prioritization for districts that receive an offer from more than one high-performing or other community school. If a district receives notice from more than one high-performing community school, it must hold an auction at which only those interested high-performing community schools may bid. If no such high-performing community school expresses interest, the district may move on to the non-high-performing community schools and college-prep boarding schools. If two or more of these schools express interest, the district must hold an auction at which only the interested schools would participate.

If no community school or boarding school expresses interest, the district must hold a public auction for the property with at least 30 days’ prior notice in a newspaper of general circulation in the district. If no bids are accepted through the auction, the district may then sell the property at private sale on its own terms.

ODE will continue to maintain and publish the list of high-performing community schools.

Competitive Bidding Threshold Increased

The threshold for competitive bidding with construction projects was increased in Senate Bill 3, which became effective March 16. Under the new law, construction or demolition projects in excess of $50,000 (the previous threshold was $25,000) must be advertised for bids. All other provisions of R.C. 3313.46 remain the same.

Note about Personal Property

District-owned personal property valued at more than $10,000 is required to be sold at public auction after 30 days’ notice. This statute has not changed (R.C. 3313.41). If a district adopts a resolution that school district property worth less than $2,500 (fair market value) is obsolete or unneeded, it may donate that property to eligible nonprofit entities. The board must adopt a procedure and must publish its intent to donate in a newspaper. Contact an Ennis Britton attorney for the specific requirements and applicability of the law to any personal property being considered for sale or disposal.

by Pamela Leist | Mar 24, 2017 | Board Policy & Representation, General, Legislation, School Management

Senate Bill 199, which was passed during the lame duck session and signed by the governor in December, significantly expands the rights of certain individuals to possess weapons on public school grounds.

State law generally prohibits an individual from conveying or possessing a deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance in a school safety zone (R.C. 2923.122). R.C. 2901.01 defines a school safety zone to include a school, school building, school premises, school activity, and school bus. Violators may be charged with misdemeanor or felony criminal offenses.

There are a few exceptions to this prohibition, including one that grants a school district board of education the authority to issue written permission for an individual to possess a weapon on school grounds. Additional, narrowly tailored exceptions apply for police officers, security personnel, school employees, and students under certain circumstances. The new law further expands these exceptions in three key areas.

First, the bill specifically authorizes an individual to possess a concealed handgun in a school safety zone as long as the individual either remains in a motor vehicle with the gun or leaves the gun behind in the locked vehicle. For this exception to apply, the individual must have an active concealed-carry permit or must be an active-duty member of the armed forces who is carrying a valid military identification card and documentation of successful completion of firearms training (the training must meet or exceed requirements for concealed permit holder training).

Next, the new law expands the right of law enforcement officers to carry a deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance in a school safety zone at any time regardless of whether the officer is on active duty. The prior version of the law limited such rights to law enforcement officers who were on active duty only.

Finally, the new law now permits the possession and use of an object indistinguishable from a firearm during a school safety training.

The law became effective March 21, 2017. School districts should review board policies that regulate use and possession of weapons on school grounds and should contact legal counsel with questions about how the law will impact district operations.

by Gary Stedronsky | Nov 29, 2016 | General

A federal judge in Texas has granted a nationwide temporary injunction in response to a lawsuit filed by 21 states, including Ohio, to challenge the new Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) overtime rule. The court agreed with the plaintiff states that the new rule could cause irreparable harm if it was not stopped before it was scheduled to go into effect on December 1, 2016, saying that the Department of Labor (DOL) exceeded the authority it was delegated by Congress in issuing this overtime rule.

Under the new overtime rule, “white collar” salaried employees not otherwise exempt from overtime pay would be eligible for overtime pay if their weekly salary is less than $913, which equals $47,476 when calculated on an annual basis – doubling the previous salary threshold.

Although application of the new rules has been stayed, school districts should continue to track eligible employees’ hours and maintain meticulous payroll records. They should also require that employees submit time records.

Districts should be mindful that the new rule would affect only the salary threshold component of the overtime-exemption test – a two-part test that requires that employees meet the salary threshold as well as perform duties that are exempt under FLSA. Therefore, employees who meet the lower salary threshold ($23,660 annually) must also perform exempt duties for the overtime exemption to apply. Employees who perform nonexempt job duties are eligible for overtime regardless of their salary.

Ennis Britton attorneys are available to help with any questions regarding the overtime rule, the injunction, which employees are affected, how to maintain payroll records, and how the two-part salary–duties test applies.

Ryan M. LaFlamme served as a law clerk for the firm during law school before joining the firm as an attorney. He is a member of the firm’s Construction and Real Estate, School Finance, and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and practices in many areas of the law concerning school districts including employment issues, construction, student discipline, workers’ compensation, labor arbitration, staff discipline, and policy review and drafting, in addition to general school law and local government practice. Ryan also serves as assistant prosecutor for two municipalities in Ohio. He has represented school district boards of education in both state and federal court. He has also defended school boards before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the state and federal Offices for Civil Rights, the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation Review Commission, and the Unemployment Review Commission.

Ryan M. LaFlamme served as a law clerk for the firm during law school before joining the firm as an attorney. He is a member of the firm’s Construction and Real Estate, School Finance, and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and practices in many areas of the law concerning school districts including employment issues, construction, student discipline, workers’ compensation, labor arbitration, staff discipline, and policy review and drafting, in addition to general school law and local government practice. Ryan also serves as assistant prosecutor for two municipalities in Ohio. He has represented school district boards of education in both state and federal court. He has also defended school boards before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the state and federal Offices for Civil Rights, the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation Review Commission, and the Unemployment Review Commission. Pamela A. Leist served as a law clerk for the firm before joining the firm as an attorney. She is a member of the Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and assists clients with a variety of education law issues including special education, student discipline, labor and employment law, negotiations, board policy review and development, and legislative review. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. She also serves as the firm’s marketing coordinator.

Pamela A. Leist served as a law clerk for the firm before joining the firm as an attorney. She is a member of the Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams and assists clients with a variety of education law issues including special education, student discipline, labor and employment law, negotiations, board policy review and development, and legislative review. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. She also serves as the firm’s marketing coordinator. Giselle S. Spencer is a member of the firm’s Special Education, Workers’ Compensation, and Finance Practice Teams. She counsels school district boards of education and administration on many aspects of education law including employment matters, workers’ compensation, property valuation, student discipline, public records, special education, discrimination complaints, and board governance. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, county Boards of Revision, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Industrial Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. Prior to entering private practice, Giselle served as director of legal services for Dayton Public Schools and chief legal counsel for Columbus Public Schools. She has also served as chief examiner for the Dayton Civil Service Commission.

Giselle S. Spencer is a member of the firm’s Special Education, Workers’ Compensation, and Finance Practice Teams. She counsels school district boards of education and administration on many aspects of education law including employment matters, workers’ compensation, property valuation, student discipline, public records, special education, discrimination complaints, and board governance. She has represented boards of education before state and federal courts, county Boards of Revision, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Industrial Commission, the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, the State Personnel Board of Review, the State Employment Relations Board, the Ohio Unemployment Review Commission, and the Ohio Department of Education. Prior to entering private practice, Giselle served as director of legal services for Dayton Public Schools and chief legal counsel for Columbus Public Schools. She has also served as chief examiner for the Dayton Civil Service Commission. Erin Wessendorf-Wortman advises clients on a variety of education law matters including labor and employment issues, student discipline and rights, special education, relationships with school resource officers, serving transgender students, employee misconduct and investigations, and general school law practice. She is also a member of the firm’s Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams. Erin has represented school boards before a variety of federal and state administrative agencies including the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, State Employment Relations Board, Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.

Erin Wessendorf-Wortman advises clients on a variety of education law matters including labor and employment issues, student discipline and rights, special education, relationships with school resource officers, serving transgender students, employee misconduct and investigations, and general school law practice. She is also a member of the firm’s Special Education and Workers’ Compensation Practice Teams. Erin has represented school boards before a variety of federal and state administrative agencies including the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, State Employment Relations Board, Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. Megan Bair Zidian advises public school districts and boards of education on a variety of education law matters including collective bargaining, labor and employment issues, student discipline and privacy issues, special education and board policy, and administrative guideline development. She is a member of the firm’s Special Education and School Finance Practice Teams. She has defended boards of education in arbitration, special education due process hearings, and state and federal administrative agencies including the State Employment Relations Board, Ohio Civil Rights Commission, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Office for Civil Rights. Megan also has extensive experience in the school transformation process and assists academically distressed districts in navigating that progression.

Megan Bair Zidian advises public school districts and boards of education on a variety of education law matters including collective bargaining, labor and employment issues, student discipline and privacy issues, special education and board policy, and administrative guideline development. She is a member of the firm’s Special Education and School Finance Practice Teams. She has defended boards of education in arbitration, special education due process hearings, and state and federal administrative agencies including the State Employment Relations Board, Ohio Civil Rights Commission, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Office for Civil Rights. Megan also has extensive experience in the school transformation process and assists academically distressed districts in navigating that progression.