by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | May 31, 2017 | Board Policy & Representation, Labor and Employment

In our May issue of School Law Review, we covered important dates and procedures for teacher nonrenewal, including the required May dates for evaluations. Unless a collective bargaining agreement provides otherwise, a board of education that wishes to nonrenew a teacher must evaluate the teacher in accordance with R.C. 3319.111, which provides that observations for teacher evaluations must be completed by May 1 and that teachers must receive a written report of their evaluation results by May 10.

In June and July are other important dates on teacher nonrenewal and resignation. Check your collective bargaining agreement for any additional requirements or timelines that must be met. Below are important dates and procedures on handling changes in teaching staff.

- June 1: Deadline for employers to submit written notice of intent to nonrenew a teacher.

- July 10: Deadline for teachers to submit notice of resignation. After this date, a board of education is not obligated to release teachers from their contract.

Resignations

A teacher may rescind notice of resignation only if it has not been formally accepted by the board. After the board accepts a resignation, the teacher may not withdraw the resignation.

Licensure of New Hires

New teachers’ licenses must be effective as of their first day on the job, regardless of whether class is in session. A board of education is not authorized by law to pay a teacher unless the teacher holds an effective state-issued license. Treasurers and superintendents should check each newly hired teacher’s license for verification of the effective date of licensure. Contact an Ennis Britton attorney if your district has any issues with teacher licenses in pending status.

Nonrenewal Procedure: Timeline

- The nonrenewal process begins when the board of education passes a resolution not to renew a contract and the treasurer sends notice of the decision to the teacher.

- Within 10 days of receipt of the notice of nonrenewal, a teacher may file with the treasurer a written demand for a description of the circumstances that led to the board’s decision to nonrenew the teacher.

- Within 10 days of receipt of the written demand, the treasurer must provide the teacher with this written statement of circumstances. This statement sets forth the substantive basis for the nonrenewal and must also expressly state the reasons for the nonrenewal.

- Within 5 days of receipt of the statement of circumstances, the teacher may file with the treasurer a written demand for a hearing before the board of education.

- Within 10 days of receipt of written demand for a hearing, the treasurer must provide the teacher with a written notice of the time, date, and place of the hearing. The hearing must be conducted within 40 days of the date on which the treasurer received the demand for a hearing (see below for more on the hearing).

- Within 10 days of the hearing, the board must issue a written decision to the teacher either affirming or vacating its intention not to renew.

- Within 30 days after receipt of the written decision, the teacher may file an appeal in the court of common pleas.

Nonrenewal Hearings

A nonrenewal hearing before the board of education must be conducted by a majority of the members of the board of education. The statute does not permit a designee to conduct the hearing. The hearing must be held in executive session unless both the board and the teacher agree to hold it in public. The board members, teacher, superintendent, assistant superintendent, legal counsel for the board, legal counsel or other representative of the teacher, and any person designated to make a record of the hearing may attend the hearing held in executive session.

The content, purpose, and procedures for the hearing are not addressed in the Ohio statute. However, the Ohio Supreme Court has held that the hearing should be more than an informal opportunity for the teacher to express objections to the board’s decision. Therefore, the nonrenewal hearing should contain, at a minimum, the presentation of evidence, the examination of witnesses, and a review of the parties’ arguments. Other Ohio courts have held that evidence is not limited to the current school year but may include that from previous school years as well. Based on the hearing, the board will either affirm or vacate its intention not to reemploy the teacher.

Appeals

If the board affirms its intention to nonrenew, the teacher may appeal the board’s decision to the court of common pleas. The court of common pleas is generally limited to determining if the district made procedural errors during the nonrenewal. The teacher may not challenge the board’s decision, and the court may not consider the merits of the board’s reasons. Therefore, the court may order that the teacher be reinstated only if it finds that the evaluation procedures were not followed or that the teacher was not provided with written notice of intent to nonrenew by June 1. If the court finds that either of these violations has occurred, it may reinstate the teacher but is not required to do so.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | May 23, 2017 | General, Student Education and Discipline

In a unanimous opinion, the Ohio Supreme Court has held that a school’s search of an unattended bag, and the two subsequent searches that initiated from the initial search, were constitutional. The court held that the searches served a compelling governmental interest in protecting the safety of the students. Two lower courts had ruled that the subsequent searches were unconstitutional and thus suppressed the evidence found in those searches – including ammunition and a gun.

Whetstone High School student James Polk left a book bag on his school bus. The bus driver found the book bag and gave it to the safety and security resource coordinator, Robert Lindsey, who checks the buses to ensure that no students are remaining on board. Lindsey was not a police officer. Based on the high school’s practice of searching unattended book bags to identify the owner and to ensure the contents are not dangerous, Lindsey opened the bag and saw some papers and notebooks, along with Polk’s name written on one of the papers (search 1). He had heard that Polk was possibly in a gang, so he took the bag immediately to the principal’s office, where together they conducted a complete search of the book bag (search 2).

In conducting search 2, the principal and Lindsey found bullets in the book bag and then contacted a police officer. When the police officer arrived, they found Polk and searched him and the book bag he was carrying (search 3). They found a handgun in the book bag during search 3.

On trial for conveyance or possession of a deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance in a school-safety zone, Polk asked the court to suppress the evidence – both the bullets and the handgun – arguing that the searches were unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment, which protects from unreasonable searches and seizures. Both the trial court and the court of appeals granted his motion to suppress the evidence, holding that search 1 – Lindsey’s initial opening of the bag enough to see Polk’s name on a document – was the only legitimate search. The other two searches, the courts held, were unconstitutional.

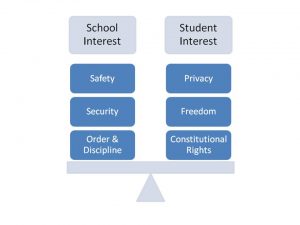

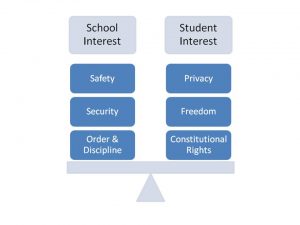

In general, under the Fourth Amendment, a police officer must have probable cause and a search warrant to conduct a search. However, courts have held that school searches may be conducted under a lesser standard of reasonable suspicion: justified at inception and reasonable in scope. In this case, the Ohio Supreme Court was tasked with determining whether the search protocol used was reasonable through balancing the government’s interest in safety and security against the student’s privacy interests.

The court centered on the constitutionality of search 2: whether it was permissible for the principal and Lindsey to conduct a full search of the student’s bag, when search 1 provided them with the identity of the owner of the unattended book bag.

In its finding, the court determined that it was appropriate for Whetstone High School to conduct complete searches of unattended book bags to ensure that they do not contain dangerous contents. Anything less than a complete search would not be enough to ensure safety and security for students. Key to this determination was that Whetstone High School required searches of unattended book bags to not only identify the owners but also to verify that the contents of the book bag are not dangerous. This was their protocol, albeit unwritten. Further, the search protocol was appropriate, reasonable, and reflective of the school’s obligation to keep students safe in a time when schools face a myriad of security concerns (e.g., school shootings, bomb threats, terrorist attacks). As a result, search 1 was inadequate in the court’s mind as it did not advance the school’s interest in ensuring safety and security of its students. Search 2 was required to fulfill this interest.

Additionally, the court found that the student’s expectation of privacy in his unattended book bag was “greatly diminished.” A person’s reasonable expectation of privacy diminishes when an item is lost or unattended, to the extent that the contents may be examined by the person who has found the item. Furthermore, a lost item in a closed container such as a book bag would carry an even lesser expectation of privacy, especially in a school setting, which must ensure the safety and security of all students.

Therefore, in balancing the school’s strong interest in protecting its students against Polk’s low expectation of privacy in the unattended book bag, the court determined that search 2 was reasonable and appropriate because the school needed to not only identify the owner of the book bag but also ensure the contents of the book bag were not dangerous. The court did not comment on search 3 but instead left the resulting judgment on that search to the lower court to make, consistent with this new decision.

State v. Polk, Slip Opinion No. 2017-Ohio-2735.

by Ryan LaFlamme | May 16, 2017 | Labor and Employment, Workers’ Compensation

The Supreme Court of Ohio recently issued an opinion in a workers’ compensation case in which an employer was sued for disability payments even after the employee had quit and moved on to another job.

The employee, Norman James Jr., worked for Walmart at the time he was injured. The injury fractured a surgical screw in his neck from a prior surgery, and he was allowed some compensation for certain conditions related to that injury. He returned to work after being fully released by his doctor, and then he quit his job one-and-a-half years later. He briefly worked at Petco and then began working for Casper Service Automotive. After a few months he was fired from Casper for excessive absenteeism.

More than a year later, James filed a motion for temporary total disability (TTD) payments against Walmart – retroactive to the day after he was fired from Casper. Walmart contested the claim on the grounds that the medical evidence did not support an award and that James had voluntarily abandoned his job when he was fired for cause from Casper.

If an injured worker does not return to his or her former position of employment as a result of the worker’s own actions rather than the industrial injury, the worker is considered to have voluntarily abandoned his or her employment and is no longer eligible for TTD compensation. However, an injured worker who voluntarily abandons employment but reenters the workforce will be eligible to receive TTD compensation from the original employer if, due to the original industrial injury, the claimant becomes temporarily and totally disabled while working at the new job. Thus, James had the burden of proving that his termination from Casper for excessive absences was due to his industrial injury at Walmart.

The Industrial Commission ruled against James, finding that the medical evidence did not support his claim. The next month, James again filed a request for TTD. This time, the hearing officer ruled that the matter had already been adjudicated, that James had voluntarily abandoned his job at Casper, and that he was not employed by either Casper or Walmart when his alleged disability recurred.

James then filed a mandamus action in the court of appeals, challenging the Industrial Commission’s ruling. The magistrate affirmed the Industrial Commission’s ruling, and the employee filed objections. The court of appeals agreed that James had voluntarily abandoned his employment at Walmart, but it sent the case back to the Industrial Commission to hear further evidence as to whether the employee was fired from Casper or laid off.

After an unsuccessful attempt at mediation, the case then came to the Ohio Supreme Court by way of appeals. The Supreme Court found that James had voluntarily quit his job at Walmart because his departure was not due to his industrial injury but rather so that he could pursue other employment. The court distinguished the case relied on by the employee, in which employees were laid off after their injuries, finding that James had presented no evidence that his industrial injury caused the excessive absences for which he was fired: “[A] key tenet in temporary-total-disability cases is that ‘the industrial injury must remove the claimant from his or her job. This requirement obviously cannot be satisfied if the claimant had no job at the time of the alleged disability.’”

Districts should be aware that they may have liability for TTD claims even after an injured worker has moved on to other employment. An employer would certainly be liable if the industrial injury is the cause of the departure – whether from the current or a subsequent employer – even if an employee is terminated for excessive absences. If the absences are caused by the industrial injury, the employee may be entitled to TTD. However, if the separation is not caused by the industrial injury, the employee is not losing wages due to the injury, and so no TTD can be awarded. TTD would also be denied, as in this case, where a new period of disability begins without the employee having a job at the time.

– State ex rel. James v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., Slip Opinion No. 2017-Ohio-1426.