by Bill Deters | Aug 31, 2017 | Legislation, Student Education and Discipline

House Bill 49, the budget bill, provides two additional pathways for graduation for the class of 2018. In short, the first option is an academic pathway, and the second is a career-tech pathway. (See also the Ennis Britton blog post on the new graduation requirements.)

Note: This applies only to the class of 2018, or as the bill states, to students who entered ninth grade for the first time on or after July 1, 2014, but prior to July 1, 2015.

Academic Pathway

In addition to meeting other graduation requirements as follows:

- Take all end-of-course exams (or the private charter school assessment)

- Retake at least once any end-of-course exam in English language arts or math on which the student scored lower than 3

- Complete the required units of instruction

a student must meet two of the following requirements:

- Have an attendance rate of at least 93 percent during 12th grade

- Take at least four full-year or equivalent courses during 12th grade and has at least a 2.5 GPA (on a 4.0 scale) for the 12th-grade courses

- Complete a capstone project during 12th grade

- Complete 120 hours of work in a community service role or in a position of employment, including internships, work study, co-ops, and apprenticeships

- Earn 3 or more transcripted credit hours under College Credit Plus at any time during high school

- Pass an AP or IB course and receive a score of 3 or higher on the corresponding AP exam or 4 or higher on the corresponding IB exam at any time during high school

- Earn at least a Level 3 score in each of the Reading for Information, Applied Mathematics, and Locating Information components of the job skills assessment, or a comparable score on similar components of a succeeding version of that assessment

- Obtain an industry-recognized credential or a group of credentials equal to at least 3 points total

- Satisfy the conditions required to receive the OhioMeansJobs-readiness seal

Career-Tech Pathway

In addition to meeting other requirements as follows:

- Take all end-of-course exams (or the private charter school assessment)

- Complete the required units of instruction

- Complete an ODE-approved career-tech training program that includes at least four career-tech courses

a student must meet one of the following requirements:

- Attain a cumulative score of at least proficient on required career-tech assessments or test modules

- Obtain an industry-recognized credential or group of credentials worth 12 points

- Demonstrate successful workplace participation, based on a written agreement signed by the student, a district representative, and an employer or supervisor, by completing 250 hours of workplace experience and receiving regular, written, positive evaluations from the employer or supervisor and a district representative

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | May 23, 2017 | General, Student Education and Discipline

In a unanimous opinion, the Ohio Supreme Court has held that a school’s search of an unattended bag, and the two subsequent searches that initiated from the initial search, were constitutional. The court held that the searches served a compelling governmental interest in protecting the safety of the students. Two lower courts had ruled that the subsequent searches were unconstitutional and thus suppressed the evidence found in those searches – including ammunition and a gun.

Whetstone High School student James Polk left a book bag on his school bus. The bus driver found the book bag and gave it to the safety and security resource coordinator, Robert Lindsey, who checks the buses to ensure that no students are remaining on board. Lindsey was not a police officer. Based on the high school’s practice of searching unattended book bags to identify the owner and to ensure the contents are not dangerous, Lindsey opened the bag and saw some papers and notebooks, along with Polk’s name written on one of the papers (search 1). He had heard that Polk was possibly in a gang, so he took the bag immediately to the principal’s office, where together they conducted a complete search of the book bag (search 2).

In conducting search 2, the principal and Lindsey found bullets in the book bag and then contacted a police officer. When the police officer arrived, they found Polk and searched him and the book bag he was carrying (search 3). They found a handgun in the book bag during search 3.

On trial for conveyance or possession of a deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance in a school-safety zone, Polk asked the court to suppress the evidence – both the bullets and the handgun – arguing that the searches were unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment, which protects from unreasonable searches and seizures. Both the trial court and the court of appeals granted his motion to suppress the evidence, holding that search 1 – Lindsey’s initial opening of the bag enough to see Polk’s name on a document – was the only legitimate search. The other two searches, the courts held, were unconstitutional.

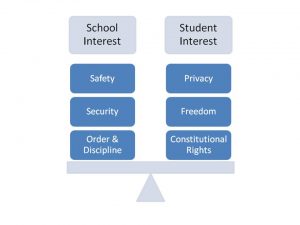

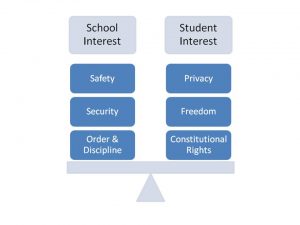

In general, under the Fourth Amendment, a police officer must have probable cause and a search warrant to conduct a search. However, courts have held that school searches may be conducted under a lesser standard of reasonable suspicion: justified at inception and reasonable in scope. In this case, the Ohio Supreme Court was tasked with determining whether the search protocol used was reasonable through balancing the government’s interest in safety and security against the student’s privacy interests.

The court centered on the constitutionality of search 2: whether it was permissible for the principal and Lindsey to conduct a full search of the student’s bag, when search 1 provided them with the identity of the owner of the unattended book bag.

In its finding, the court determined that it was appropriate for Whetstone High School to conduct complete searches of unattended book bags to ensure that they do not contain dangerous contents. Anything less than a complete search would not be enough to ensure safety and security for students. Key to this determination was that Whetstone High School required searches of unattended book bags to not only identify the owners but also to verify that the contents of the book bag are not dangerous. This was their protocol, albeit unwritten. Further, the search protocol was appropriate, reasonable, and reflective of the school’s obligation to keep students safe in a time when schools face a myriad of security concerns (e.g., school shootings, bomb threats, terrorist attacks). As a result, search 1 was inadequate in the court’s mind as it did not advance the school’s interest in ensuring safety and security of its students. Search 2 was required to fulfill this interest.

Additionally, the court found that the student’s expectation of privacy in his unattended book bag was “greatly diminished.” A person’s reasonable expectation of privacy diminishes when an item is lost or unattended, to the extent that the contents may be examined by the person who has found the item. Furthermore, a lost item in a closed container such as a book bag would carry an even lesser expectation of privacy, especially in a school setting, which must ensure the safety and security of all students.

Therefore, in balancing the school’s strong interest in protecting its students against Polk’s low expectation of privacy in the unattended book bag, the court determined that search 2 was reasonable and appropriate because the school needed to not only identify the owner of the book bag but also ensure the contents of the book bag were not dangerous. The court did not comment on search 3 but instead left the resulting judgment on that search to the lower court to make, consistent with this new decision.

State v. Polk, Slip Opinion No. 2017-Ohio-2735.

by Bronston McCord | Nov 1, 2016 | General, Student Education and Discipline

Beginning with the class of 2018, Ohio’s graduation requirements will change. In addition to the state’s academic curriculum requirements, which have not changed, students must fulfill an additional requirement to earn their high school diploma. Students have three options to choose from to fulfill this additional requirement. (Note: The Ohio Graduation Tests are still in use for the class of 2017; however, these students may use the new end-of-course tests to satisfy the testing requirement.)

- Ohio’s State Tests: Meet the minimum number of points on end-of-course tests

Under this option, students must accumulate at least 18 total points on the seven state tests, with a minimum number of points in each of the three subject areas. The points given for each test range from 1 (limited performance level) to 5 (advanced performance level).

|

Subject Area

|

Courses Tested

|

Number of Tests

|

Minimum Points Required

|

Points Possible

|

| English |

English I |

2 |

4 |

10 |

| English II |

| Math |

Algebra I or

Intermediate Math I |

2 |

4 |

10 |

Geometry or

Intermediate Math II |

| Science and Social Studies |

Biology (or Physical Science – 2018 only) |

3 |

6 |

15 |

| American History |

| American Government |

| Additional points required from any of the above tests |

4 |

|

| Total Points |

18 |

35 |

This option gives students flexibility in which subject areas to earn points – as long as the minimum number of points is met in each subject area. Thus, a high score in one subject area can help to offset a lower score in another subject area.

Retakes: Students may retake any test anytime during the student’s academic career within the testing window offered by ODE.

Alternatives for Science and Social Studies tests: Instead of taking the state’s end-of-course tests in Science and Social Studies, the following alternative options are available:

- Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate courses: The tests offered in these courses will substitute for the end-of-course tests.

- College Credit Plus courses: The grade earned in the college course will determine the number of points credited to the test.

- College Readiness Tests: Meet the minimum scores on the ACT or SAT test

Under this option, students may meet or exceed the minimum score requirements on the ACT or SAT tests. (Note: These minimum scores are known as “remediation-free” scores, which are set by Ohio’s college and university presidents; therefore, they are subject to change.)

|

ACT

|

SAT

|

| Subject Area |

Minimum Score |

Subject Area |

Minimum Score |

| English |

18 |

Writing |

430 |

| Math |

22 |

Math |

520 |

| Reading |

22 |

Reading |

450 |

- Industry Credential and Work Readiness: Earn an industry credential and meet the minimum score on the WorkKeys test

Under the credential option, students graduate high school ready to enter the workforce with a job skill that Ohio employers need right now. Students must earn a minimum of 12 points from an approved, industry-recognized credential or group of credentials in a single career field, and then score 13 or greater on a job-skills test, WorkKeys, which shows their work-readiness in that job.

Students can choose from 13 career fields:

- Agriculture

- Arts and Communications

- Business and Finance

- Construction

- Education and Training

- Engineering

- Health

- Hospitality and Tourism

- Human Services

- Information Technology

- Law and Public Safety

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

|

WorkKeys Test

|

| Subject Area |

Minimum Points Required |

| Reading |

3 |

| Applied Mathematics |

3 |

| Locating Information |

3 |

| Additional points required from any of the above areas |

1 (class of 2018 and 2019) |

| 2 (beginning class of 2020) |

| Total Points |

13 (2018/2019) |

| 14 (2020) |

by Pamela Leist | Sep 26, 2016 | General, Special Education, Student Education and Discipline

A school district’s authority to discipline a student for off-campus speech is an increasingly relevant concern today for public schools. Inappropriate or offensive speech can cause lasting injury to victims and can trigger significant community backlash and unrest. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals recently addressed this issue in a case that arose out of Oregon.

The case was filed after a school district suspended a seventh-grade student named C.R. for harassing two other students from school. C.R. and some of his friends had been involved in an escalating series of encounters with two sixth-grade students, a girl and a boy, both disabled, first calling them vulgar names and later increasing to sexual taunting. On the day of the incident at issue, the students were traveling home from school through a public park adjacent to school property, just a few hundred feet from the campus. About five minutes after school let out, C.R. and his friends circled around the two younger students, commenting and questioning them about sexual acts and pornography. A school employee rode by the students on her bicycle, noticed the group, and stopped to help the younger girl and boy. The girl reported that the encounter made her feel unsafe, and the employee walked the two students home.

After investigating the incident, school administrators concluded that C.R. was the “ringleader” of the group and that the conduct fell within the district’s definition of sexual harassment. All of the boys were disciplined. C.R. was suspended for two days, not only because of the harassment but also because he had lied to administrators during the investigation and had disregarded their request to not discuss the interview with his friends.

C.R.’s parents filed a lawsuit a year after the incident, alleging that his First Amendment and due process rights had been violated and that the school lacked authority to discipline him. The school district moved for summary judgment, which was granted by the district court. The parents appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit, which considered the following.

Was C.R.’s conduct sexual harassment? The school had a policy that defined sexual harassment, and the investigation had yielded evidence that C.R.’s behavior fit within that definition. The Ninth Circuit Court noted, “Federal courts owe significant deference to a school’s interpretation of its own rules and policies. … We uphold a school’s disciplinary determinations so long as the school’s interpretation of its rules and policies is reasonable, and there is evidence to support the charge.” Therefore, the court upheld the district’s conclusion that C.R.’s behavior was considered sexual harassment.

Could the school regulate his speech and discipline him? The court first considered whether the school could permissibly regulate the student’s off-campus speech at all, and then considered whether the school’s regulation of the student’s speech complied with the requirements of the First Amendment.

Regulation of students’ on-campus speech is well established as constitutional; however, regulation of off-campus speech is another matter. Following a previous Supreme Court decision (Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969)), regulation of student speech is permissible if the speech “might reasonably lead school authorities to forecast substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities” or if the speech might collide “with the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone.” Speech that is merely offensive is not sufficient; however, sexually harassing speech is more than that. Sexually harassing speech, the court held, implicates other students’ rights to be secure, threatening their sense of physical, emotional, and psychological security.

The age of the student who is being harassed is also relevant. The Supreme Court has noted that children younger than age 14 are less mature, and therefore overtly sexual speech could be more seriously damaging to them. For this reason, elementary schools may exercise greater control over student speech than secondary schools.

The court held that the school district did indeed have the authority to discipline C.R. for his harassing speech, even if it was off campus, for a number of reasons:

- All of the individuals involved were students

- The incident took place –

- On the students’ walk home

- A few hundred feet from school

- Immediately after school let out

- On a path that begins at the school

- The students were together on the path because of school

Succinctly stated, the court held that “a school may act to ensure students are able to leave the school safely without implicating the rights of students to speak freely in the broader community.”

Were C.R.’s due process rights violated? Again citing previous court decisions, the opinion noted that the Constitution allows informal procedures when a student suspension is 10 days or fewer. The school must provide the student notice of the charges but need not outline specific charges and their potential consequences or notify parents of the charges prior to the suspension. If the student denies the charges, the student then must have an opportunity to explain his side of the story. A school is not constitutionally required to inform the student of the specific rules or policies in question. For these reasons, the court held that the school did not violate C.R.’s procedural due process rights.

C.R. also claimed that his substantive due process rights were violated when the school recorded the reason for suspension as “harassment – sexual,” which allegedly deprived him of a good reputation. The court opined that C.R. did not have a genuine interest in maintaining a good reputation, as he had since stolen supplies from the school, and held that the school may record the reason for suspension, “however unsavory,” so long as it applied appropriate procedural safeguards. Therefore, the school also did not violate his substantive due process rights.

Ultimately, the Ninth Circuit upheld the summary judgment that the district court had previously granted.

C.R. v. Eugene School District 4J, No. 13-35856 (9th Cir. 2016)

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | Aug 17, 2016 | Student Education and Discipline

In December 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized the McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youths program. Updated guidance was released by the U.S. Department of Education to help school districts understand the amendments to the McKinney-Vento Act, which will take effect October 1, 2016. These changes include the following:

- Greater emphasis on identifying homeless children and youths, requiring that state and local education agencies provide training for staff members to best meet the unique needs of homeless students.

- A focus on ensuring that eligible homeless students have access to academic and extracurricular activities, including magnet schools, summer school, career and technical education, advanced placement, online learning, and charter school programs.

- Ensuring that homeless children and youths remain in their school of origin, which is defined as the school the student attended when permanently housed. The student must be able to remain at this school for the duration of homelessness, or until the end of the school year during which they become permanently housed once more.

- Dispute resolution procedures which now address eligibility issues, school choice, and enrollment. In the event of a dispute between a parent, guardian, or youth and the local educational agency, the student must be immediately enrolled in the school in which he or she sought placement. The student must also be provided transportation to or from the school of origin for the duration of the dispute, at the request of the parent, guardian, or local liaison representing an unaccompanied youth.

- New authority for local liaisons to confirm the eligibility of homeless children and youths for programs offered through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

This guidance and the amended McKinney-Vento Act aim to equip schools with the necessary tools they need to best serve homeless students and ensure that they continue to receive an education. More information and advice for helping homeless students can be found in a fact sheet released by the U.S. Department of Education. If you have questions on how these changes can be implemented within your school district, please contact an Ennis Britton attorney.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | Aug 12, 2016 | Board Policy & Representation, Student Education and Discipline

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits discrimination against students on the basis of sex for schools that receive federal funding. More recently, the definition of “sex” discrimination was expanded by federal regulatory agencies. In April 2014, the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (OCR) indicated that Title IX’s sex discrimination prohibition extends to discrimination “based on gender identity or failure to conform to stereotypical notions of masculinity or femininity.” In this guidance, OCR informed school districts that discrimination against students who identify as being transgender, whether in the curricular setting or in extracurricular activities, is prohibited.

This guidance was later reinforced when the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice issued joint guidance in May 2016 stating that both federal agencies will treat a student’s gender identity as the student’s sex for purposes of enforcing Title IX.

Therefore, according to the Education and Justice Departments’ interpretation and application of Title IX, school districts need to provide accommodations for transgender students. Ennis Britton has advised that decisions regarding transgender students be made on a case-by-case basis and in a team environment, wherein the parents, student, and administration may discuss the transition process for that student and the appropriate accommodations.

However, on August 3, 2016, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) issued an order that has caused a number of school districts to question their compliance with the Education and Justice Departments’ previous guidance. The SCOTUS order has temporarily stopped the enforcement of a lower federal court order that directed a school district in Virginia to permit a transgender male to use the boys’ bathroom at his school. Gloucester County Sch. Bd v. G.G., 579 U.S. ___ (2016).

The SCOTUS order did not reverse or overrule the guidance, interpretation, or application of Title IX that is being promulgated and enforced by the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice. Rather, the SCOTUS order maintained the status quo for that student and that Virginia school while the case plays out in the lower courts.

Caution should be exercised in reading too much into this SCOTUS order for a number of reasons. First, the deciding vote of Justice Breyer was a “courtesy.” His vote should not be preliminarily construed to be in alignment with four other justices as it relates to accommodations of transgender students in schools. Second, this order does not put a hold on the guidance set forth by the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice. The order applies to the one student involved, G.G., and to the Virginia school seeking to deny the student accommodations within its buildings. Finally, the guidance from the Education and Justice Departments still exists and can be expected to be enforced.

School districts should consult legal counsel in determining how best to maneuver the legal, social, and political landscapes when considering if and how to accommodate transgender students within their schools. Special consideration should be given to the fact that without a stay on the guidance or a statement otherwise from OCR, OCR will continue to enforce its interpretation of Title IX, which will include seeking to halt federal, Title IX funds for non-compliant school districts.