by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | Feb 14, 2018 | Board Policy & Representation

On February 12, 2018, BuzzFeed News issued an article detailing an interview with U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) officials wherein the USDOE spokesperson outlined the department’s policy on how it would handle transgender student complaints. The details of this article, and statements made by the USDOE spokesperson, were later confirmed by NPR’s Education News Desk. (Please note that although BuzzFeed is not typically a news source for Ennis Britton, the details of the interview and the fact that the details were confirmed by another news source renders this information useful and informative.)

Essentially, the USDOE spokesperson has said that the USDOE will not investigate or take action on any complaints filed by transgender students who are banned from restrooms that match their gender identity. If the complaint alleges that the transgender student has been bullied, harassed, or punished due to his or her gender nonconformity, the USDOE will investigate and possibly take action against a school district.

|

Substance of Complaint

|

|

USDOE Action

|

| Alleges harassment, bullying, or punishment for failing to conform to sex-based stereotypes |

|

Will be accepted and possibly investigated by the USDOE |

| Alleges transgender student was denied access to accommodations such as restrooms and locker rooms |

|

Will not be accepted by the USDOE |

The USDOE has been noticeably silent on issues dealing with transgender students since it withdrew the May 13, 2016, Dear Colleague Letter on transgender students on February 22, 2017. The withdrawal letter can be found here. This recent interview with the USDOE spokesperson does nothing other than lay out how the USDOE will handle complaints from transgender students. This does not mean that transgender students can never bring a claim for discrimination based on their gender identity or their failure to conform to sex-based stereotypes, but it does mean that such claims will be filed in the courts as opposed to the USDOE.

This is a rather strange parsing for the USDOE and a fine line to walk in terms of what will be classified as bullying, harassment, and punishment. (See the Seventh Circuit Court case discussed below.) Districts need to be aware that if a student claims that he or she has been bullied, harassed, or punished because of being transgender or because of failure to conform to sex-based stereotypes, such a complaint must be processed and investigated pursuant to the school district’s anti-discrimination policies. Failure to do so or to take such complaints seriously could result in complaints filed with and investigated by the USDOE.

The remaining issue is accommodations – specifically, bathroom and changing/locker room access. The USDOE’s statement has made clear that this battle will occur in courts around the country as opposed to the USDOE. Therefore, it is important to see where the courts’ decisions are falling with respect to this issue around the country.

Remember, the U.S. Supreme Court canceled oral arguments in G.G. v. Gloucester County School Board, 82 F.3d 709 (4th Cir. 2016), vacated and remanded, 137 S. Ct. 1239 (U.S. 2017), remanded, 869 F.3d 286 (4th Cir. 2017), after the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice revoked the May 13, 2016, guidance from the previous administration. Based on the rescission, the U.S. Supreme Court remanded the case back down to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals to be reconsidered. The student in that case graduated in June 2017 and has since withdrawn his motion for a preliminary injunction and filed an amended complaint for nominal damages. The former student seeks a declaration that the school board violated his rights under Title IX and the Equal Protection Clause, as well as a permanent injunction preventing the school board from excluding him from using the restrooms when he is on school grounds.

In December 2016, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, relying on the now-rescinded advice, agreed with a lower court decision from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio regarding how an Ohio school district treated an eleven-year-old transgender student. The courts found that the eleven-year-old student had a strong likelihood of success in her claims against the Ohio school district and therefore should be allowed to use the school restrooms that correspond to her gender identity and otherwise be treated like other female students during the pendency of the lawsuit. However, please note although these courts have great impact and control in Ohio, they relied on the now-rescinded guidance from the USDOE, and how these courts will rule on the same issue is uncertain now that the guidance has been rescinded. Further, this case still remains to be fully and finally litigated; both the Southern District of Ohio and the Sixth Circuit ruled only on motions for an injunction; they have not yet ruled on the substantive issues at hand. This case is still pending.

Additionally, although not controlling in Ohio, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision in May 2017 (after the USDOE rescinded its previous guidance) that may be informative both in Ohio and around the country. The Seventh Circuit Court found that a school district was sex stereotyping a transgender student when it required the transgender male student to use the girls’ restroom or a private restroom. In its decision, the court held that a “policy that requires an individual to use a bathroom that does not conform with his or her gender identity punishes that individual for his or her gender non-conformance, which in turn violates Title IX” (emphasis added). The school district filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court requesting that the Court overturn the lower court’s decision. The U.S. Supreme Court granted this petition; however, the parties have since settled their dispute, agreeing on a payment of $800,000 to the student (and presumably the attorneys for fees), as well as permission for the student to use the men’s restroom if he returns to the district as an alumnus (the student graduated and no longer would be in daily attendance). As a result, although the U.S. Supreme Court will not be ruling on this case, the Seventh Circuit Court’s decision in favor of accommodating the transgender student stands.

Conclusion

In sum, the “new” information out of the USDOE does not change anything for school districts. The USDOE has simply communicated how it will handle complaints from transgender students. If the complaint deals with accommodations (restrooms, locker rooms, etc.), the USDOE will not accept the cases; but if the complaint has to do with bullying, harassment, or punishment based on transgender status, it will.

Instead, the question of whether and how to provide accommodations to transgender students will be a matter to be litigated through the court system in the years to come. For additional advice on handling requests for accommodations for transgender students or working through complaints of discrimination, please contact an Ennis Britton attorney for assistance.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | Jun 6, 2017 | Board Policy & Representation, Labor and Employment

Reversing the decision of two lower courts, the Ohio Supreme Court recently ruled that absent negotiated language in a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) limiting an arbitrator’s authority to modify a disciplinary action for just cause, an arbitrator has authority both to review the disciplinary action and to fashion a remedy that is outside the scope of the CBA.

A City of Findlay police officer was first disciplined in 2012 for conduct unbecoming. This discipline was grieved, taken to arbitration, and then modified by the arbitrator to be in line with the city’s use of a discipline matrix.

Later that same year, the same officer was found to have violated the department’s sexual harassment policy, and termination of the officer’s employment contract was recommended. The termination was grieved and taken to arbitration. The arbitrator determined that the city did not present evidence to support termination, and therefore he set aside the termination. Instead, the arbitrator determined that the disciplinary matrix could not be used, stated that a “lengthy disciplinary suspension [was] warranted,” and imposed a five-month suspension. The city appealed this decision to the county common pleas court. Both the common pleas court and the appeals court agreed with the city and found that the arbitration award did not draw its essence form the CBA and was arbitrary, capricious, and unlawful (i.e., the arbitrator overstepped his authority and power). However, the Ohio Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, on behalf of the officer, appealed these decisions to the Ohio Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court was left to determine whether the just cause discipline provision in the CBA authorized an arbitrator to change the disciplinary action recommended by the employer (in this case, the police chief using a disciplinary matrix). Key to this case was the fact that the disciplinary matrix used by the department to discipline the officer was not part of or mentioned in the CBA. Furthermore, the CBA neither mentioned the department’s disciplinary procedures nor restricted an arbitrator’s authority to review the appropriateness of the type of discipline imposed upon finding just cause for discipline. Absent this limiting language in the CBA, the arbitrator was free to fashion a remedy that he believed was appropriate.

Only Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor dissented from the court’s majority opinion, noting that the case should not have been accepted by the Supreme Court in the first place and that the majority’s decision could have unintended consequences as it seems to throw out the consideration of past practice(s). She noted that the department used the matrix as a past practice as the basis for disciplinary action, and the inability to rely on this or throw it out of consideration is dangerous. O’Connor concluded that under the majority opinion, even if a past practice is established related to disciplinary outcomes, an arbitrator could modify the discipline if the practice is shown as not specifically bargained for and incorporated into the CBA. This, in her opinion, is an undesirable result.

School districts should be aware that this holding by the Supreme Court could impact arbitrations and the review of the same by courts in Ohio. The court concluded, “Any limitation on an arbitrator’s authority to modify a disciplinary action pursuant to a CBA provision requiring that discipline be imposed only for just cause must be specifically bargained for by the parties and incorporated into the CBA.”

Ohio Patrolmen’s Benevolent Assn. v. Findlay, Slip Opinion No. 20147-Ohio-2804.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | May 31, 2017 | Board Policy & Representation, Labor and Employment

In our May issue of School Law Review, we covered important dates and procedures for teacher nonrenewal, including the required May dates for evaluations. Unless a collective bargaining agreement provides otherwise, a board of education that wishes to nonrenew a teacher must evaluate the teacher in accordance with R.C. 3319.111, which provides that observations for teacher evaluations must be completed by May 1 and that teachers must receive a written report of their evaluation results by May 10.

In June and July are other important dates on teacher nonrenewal and resignation. Check your collective bargaining agreement for any additional requirements or timelines that must be met. Below are important dates and procedures on handling changes in teaching staff.

- June 1: Deadline for employers to submit written notice of intent to nonrenew a teacher.

- July 10: Deadline for teachers to submit notice of resignation. After this date, a board of education is not obligated to release teachers from their contract.

Resignations

A teacher may rescind notice of resignation only if it has not been formally accepted by the board. After the board accepts a resignation, the teacher may not withdraw the resignation.

Licensure of New Hires

New teachers’ licenses must be effective as of their first day on the job, regardless of whether class is in session. A board of education is not authorized by law to pay a teacher unless the teacher holds an effective state-issued license. Treasurers and superintendents should check each newly hired teacher’s license for verification of the effective date of licensure. Contact an Ennis Britton attorney if your district has any issues with teacher licenses in pending status.

Nonrenewal Procedure: Timeline

- The nonrenewal process begins when the board of education passes a resolution not to renew a contract and the treasurer sends notice of the decision to the teacher.

- Within 10 days of receipt of the notice of nonrenewal, a teacher may file with the treasurer a written demand for a description of the circumstances that led to the board’s decision to nonrenew the teacher.

- Within 10 days of receipt of the written demand, the treasurer must provide the teacher with this written statement of circumstances. This statement sets forth the substantive basis for the nonrenewal and must also expressly state the reasons for the nonrenewal.

- Within 5 days of receipt of the statement of circumstances, the teacher may file with the treasurer a written demand for a hearing before the board of education.

- Within 10 days of receipt of written demand for a hearing, the treasurer must provide the teacher with a written notice of the time, date, and place of the hearing. The hearing must be conducted within 40 days of the date on which the treasurer received the demand for a hearing (see below for more on the hearing).

- Within 10 days of the hearing, the board must issue a written decision to the teacher either affirming or vacating its intention not to renew.

- Within 30 days after receipt of the written decision, the teacher may file an appeal in the court of common pleas.

Nonrenewal Hearings

A nonrenewal hearing before the board of education must be conducted by a majority of the members of the board of education. The statute does not permit a designee to conduct the hearing. The hearing must be held in executive session unless both the board and the teacher agree to hold it in public. The board members, teacher, superintendent, assistant superintendent, legal counsel for the board, legal counsel or other representative of the teacher, and any person designated to make a record of the hearing may attend the hearing held in executive session.

The content, purpose, and procedures for the hearing are not addressed in the Ohio statute. However, the Ohio Supreme Court has held that the hearing should be more than an informal opportunity for the teacher to express objections to the board’s decision. Therefore, the nonrenewal hearing should contain, at a minimum, the presentation of evidence, the examination of witnesses, and a review of the parties’ arguments. Other Ohio courts have held that evidence is not limited to the current school year but may include that from previous school years as well. Based on the hearing, the board will either affirm or vacate its intention not to reemploy the teacher.

Appeals

If the board affirms its intention to nonrenew, the teacher may appeal the board’s decision to the court of common pleas. The court of common pleas is generally limited to determining if the district made procedural errors during the nonrenewal. The teacher may not challenge the board’s decision, and the court may not consider the merits of the board’s reasons. Therefore, the court may order that the teacher be reinstated only if it finds that the evaluation procedures were not followed or that the teacher was not provided with written notice of intent to nonrenew by June 1. If the court finds that either of these violations has occurred, it may reinstate the teacher but is not required to do so.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | May 23, 2017 | General, Student Education and Discipline

In a unanimous opinion, the Ohio Supreme Court has held that a school’s search of an unattended bag, and the two subsequent searches that initiated from the initial search, were constitutional. The court held that the searches served a compelling governmental interest in protecting the safety of the students. Two lower courts had ruled that the subsequent searches were unconstitutional and thus suppressed the evidence found in those searches – including ammunition and a gun.

Whetstone High School student James Polk left a book bag on his school bus. The bus driver found the book bag and gave it to the safety and security resource coordinator, Robert Lindsey, who checks the buses to ensure that no students are remaining on board. Lindsey was not a police officer. Based on the high school’s practice of searching unattended book bags to identify the owner and to ensure the contents are not dangerous, Lindsey opened the bag and saw some papers and notebooks, along with Polk’s name written on one of the papers (search 1). He had heard that Polk was possibly in a gang, so he took the bag immediately to the principal’s office, where together they conducted a complete search of the book bag (search 2).

In conducting search 2, the principal and Lindsey found bullets in the book bag and then contacted a police officer. When the police officer arrived, they found Polk and searched him and the book bag he was carrying (search 3). They found a handgun in the book bag during search 3.

On trial for conveyance or possession of a deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance in a school-safety zone, Polk asked the court to suppress the evidence – both the bullets and the handgun – arguing that the searches were unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment, which protects from unreasonable searches and seizures. Both the trial court and the court of appeals granted his motion to suppress the evidence, holding that search 1 – Lindsey’s initial opening of the bag enough to see Polk’s name on a document – was the only legitimate search. The other two searches, the courts held, were unconstitutional.

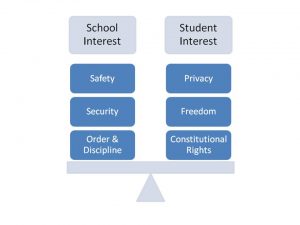

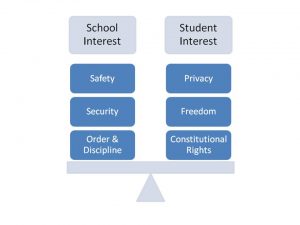

In general, under the Fourth Amendment, a police officer must have probable cause and a search warrant to conduct a search. However, courts have held that school searches may be conducted under a lesser standard of reasonable suspicion: justified at inception and reasonable in scope. In this case, the Ohio Supreme Court was tasked with determining whether the search protocol used was reasonable through balancing the government’s interest in safety and security against the student’s privacy interests.

The court centered on the constitutionality of search 2: whether it was permissible for the principal and Lindsey to conduct a full search of the student’s bag, when search 1 provided them with the identity of the owner of the unattended book bag.

In its finding, the court determined that it was appropriate for Whetstone High School to conduct complete searches of unattended book bags to ensure that they do not contain dangerous contents. Anything less than a complete search would not be enough to ensure safety and security for students. Key to this determination was that Whetstone High School required searches of unattended book bags to not only identify the owners but also to verify that the contents of the book bag are not dangerous. This was their protocol, albeit unwritten. Further, the search protocol was appropriate, reasonable, and reflective of the school’s obligation to keep students safe in a time when schools face a myriad of security concerns (e.g., school shootings, bomb threats, terrorist attacks). As a result, search 1 was inadequate in the court’s mind as it did not advance the school’s interest in ensuring safety and security of its students. Search 2 was required to fulfill this interest.

Additionally, the court found that the student’s expectation of privacy in his unattended book bag was “greatly diminished.” A person’s reasonable expectation of privacy diminishes when an item is lost or unattended, to the extent that the contents may be examined by the person who has found the item. Furthermore, a lost item in a closed container such as a book bag would carry an even lesser expectation of privacy, especially in a school setting, which must ensure the safety and security of all students.

Therefore, in balancing the school’s strong interest in protecting its students against Polk’s low expectation of privacy in the unattended book bag, the court determined that search 2 was reasonable and appropriate because the school needed to not only identify the owner of the book bag but also ensure the contents of the book bag were not dangerous. The court did not comment on search 3 but instead left the resulting judgment on that search to the lower court to make, consistent with this new decision.

State v. Polk, Slip Opinion No. 2017-Ohio-2735.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | Aug 17, 2016 | Student Education and Discipline

In December 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized the McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youths program. Updated guidance was released by the U.S. Department of Education to help school districts understand the amendments to the McKinney-Vento Act, which will take effect October 1, 2016. These changes include the following:

- Greater emphasis on identifying homeless children and youths, requiring that state and local education agencies provide training for staff members to best meet the unique needs of homeless students.

- A focus on ensuring that eligible homeless students have access to academic and extracurricular activities, including magnet schools, summer school, career and technical education, advanced placement, online learning, and charter school programs.

- Ensuring that homeless children and youths remain in their school of origin, which is defined as the school the student attended when permanently housed. The student must be able to remain at this school for the duration of homelessness, or until the end of the school year during which they become permanently housed once more.

- Dispute resolution procedures which now address eligibility issues, school choice, and enrollment. In the event of a dispute between a parent, guardian, or youth and the local educational agency, the student must be immediately enrolled in the school in which he or she sought placement. The student must also be provided transportation to or from the school of origin for the duration of the dispute, at the request of the parent, guardian, or local liaison representing an unaccompanied youth.

- New authority for local liaisons to confirm the eligibility of homeless children and youths for programs offered through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

This guidance and the amended McKinney-Vento Act aim to equip schools with the necessary tools they need to best serve homeless students and ensure that they continue to receive an education. More information and advice for helping homeless students can be found in a fact sheet released by the U.S. Department of Education. If you have questions on how these changes can be implemented within your school district, please contact an Ennis Britton attorney.