by Jeremy Neff | Oct 2, 2020 | COVID-19 (Coronavirus), General, Special Education

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) published a new COVID-19 Q&A on September 28, 2020 (OSEP QA 20-01). While OSEP explicitly cautions that the Q&A “is intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements,” it nonetheless provides insights on how long-standing rules and laws will be applied to the novel COVID-19 virus.

In support of school districts that are guiding their decision-making based on the health and safety of students and staff, OSEP repeatedly describes health and safety as “most important” and “paramount.” If a hearing officer or court is making a decision based on the equities (i.e. fairness) the emphasis of OSEP on safety will weigh in favor of schools making reasonable adjustments to how IDEA is implemented. However, OSEP also repeatedly states that school districts “remain responsible for ensuring that a free appropriate public education (FAPE) is provided to all children with disabilities.” This requires an individualized response to COVID-19 that focuses on “each child’s unique needs” and ensures “challenging objectives.”

To strike the balance of protecting health and safety while also providing FAPE, OSEP points school districts to the normal IDEA processes. The Q&A notes that no changes to the law or regulations have been made at the federal level. Interestingly, when discussing the timeline for initial evaluations OSEP advises that states “have the flexibility to establish additional exceptions” to the 60 day initial evaluation timeline. As of this writing, the Ohio Department of Education has not taken actions to allow for COVID-19 specific exceptions from the timeline.

Otherwise, OSEP’s Q&A largely points to approaches that have been addressed in prior “Special Education Spotlight” articles, Ennis Britton blog posts, and in our Coffee Chat webinar series. These approaches include conducting records review evaluations when in-person evaluations are not possible, using virtual team meeting platforms, and delivering services flexibly (e.g. teletherapy, consultation with parents.). OSEP warns against conducting remote evaluations if doing so would violate the instructions of the test publishers.

The discussion of extended school year (ESY) services is perhaps the topic most likely to generate interest in the short-term. After clearly distinguishing ESY from compensatory education or recovery services, OSEP acknowledges the authority of the states to establish standards for ESY. Note that in Ohio the standard is based on excessive regression and recoupment. OSEP proceeds to observe that, understandably, ESY services may not have been provided over the past summer due to COVID-19 restrictions. In such cases, OSEP encourages school districts to “consider” providing ESY during times such as the regular school year or scheduled breaks (e.g. winter break).

The Ennis Britton Special Education Team will continue to monitor and share with clients the latest developments as we navigate this unusual school year. Please contact a member of our team with questions or concerns.

by Jeremy Neff | Apr 17, 2020 | COVID-19 (Coronavirus), Legislation, Special Education

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was passed by Congress on March 27, 2020. Part of the act directs U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos to submit a report to Congress. The report, that must be submitted by the end of April, is to make recommendations for any additional waivers that might be needed under IDEA, in direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic. There is reason to believe that a concerted effort on the part of school districts could result in much-needed flexibility during this unprecedented time.

The National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE) and the Council of Administrators of Special Education (CASE) jointly wrote a letter in anticipation of the report the DeVos will submit. The letter asks for flexibilities for specific IDEA provisions that have been affected by COVID-19. Those provisions include timelines, procedural activities, and fiscal management. Other groups, including parent groups pushing back hard against reasonable adjustments in light of the global pandemic, are also lobbying for what flexibility should entail.

Concerns that we are hearing from clients often center on flexibility related to evaluation timelines (especially initial evaluations), recognition that what constitutes a free, appropriate, public education during the health emergency need not match what would be provided under regular operations, and realistic expectations for compensatory education upon resumption of regular school operations. If you would like to contribute to the conversation on what the flexibilities might look like, now is the time. Get in contact with professional organizations to lobby for what you feel strongly about. Your opinion matters.

by Jeremy Neff | Mar 25, 2020 | General, Special Education, Student Education and Discipline

The long-running Doe v. Ohio Department of Education litigation was back in the news earlier this month. The settlement became final and effective nearly three decades after the lawsuit was initially filed. Ennis Britton previously notified clients of the proposed settlement in December when the Ohio Department of Education’s Chief Legal Counsel sent a notice to districts that a proposed settlement has been reached. To be clear, no individual school district was a defendant in this case. Defendants included the State of Ohio, the Governor, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Ohio Department of Education. The plaintiffs – parents of students with disabilities and the students themselves – alleged that the defendants failed to ensure that students with disabilities were adequately educated in compliance with the law.

A hearing was held on February 11, 2020, to determine whether final approval would be given to the proposed settlement that circulated in December 2019. The settlement has been approved and took effect earlier this month. The settlement covers a five year period and will focus on eleven priority districts (Canton City, Cleveland Metropolitan, Columbus City, Cincinnati Public, Toledo Public, Dayton Public, Akron Public, Youngstown City, Lima City, Zanesville City, and East Cleveland City School Districts). During the settlement period, ODE will develop a plan to improve inclusion and outcomes and will implement and monitor the implementation of the plan in the priority districts.

Ennis Britton’s Special Education Team anticipates it is very likely that ideas and expectations from the plan for the eleven priority districts will have broader application in the long run. Thus, even districts that are not initially prioritized by the settlement are likely to feel the effects of the settlement. It will be important for all school districts to monitor the implementation of the settlement and to advocate for both reasonable expectations and appropriate additional funding to support whatever aspects of the settlement plan are given broader application to all of Ohio’s school districts.

Ennis Britton’s Special Education Team will continue to update our clients on the implementation of the Doe settlement.

by Erin Wessendorf-Wortman | Mar 12, 2020 | COVID-19 (Coronavirus), Special Education, Student Education and Discipline

It should come to no one’s surprise that the state and federal laws do not allow for exceptions to the required timelines for ETRs, IEPs, etc. As discussed in other posts, in December 2009, in response to the H1N1 pandemic, the U.S. Department of Education issued a memo titled “Guidance on Flexibility and Waivers for SEAs, LEAs, Postsecondary Institutions, and other Grantee and Program Participants in Responding to Pandemic Influenza (H1N1 Virus)” which plainly stated that the U.S. Department of Education would not waive the requirements for school districts to evaluate and assess during school closures. While the U.S. Department of Education issued a “Questions and Answers on Providing Services to Children with Disabilities During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak,” the Department did not issue any comments regarding IEP and 504 timelines at this time.

The Ohio Department of Education has issued its own Considerations for Students with Disabilities During Ohio’s Ordered School-Building Closure originally on March 17th, and updated on March 27th.

Proper planning on your school district’s and case manager’s part will be essential in determining how your school district needs to act as schools are currently (as of March 30, 2020) closed until May 1st during which you would may be required to have an ETR or IEP meeting.

My school district is in the middle of conducting an ETR on a student. Do we continue with this evaluation?

Based on the Guidance and Considerations, you continue with the evaluation of the student. Your district may want to consider how much of the evaluation and assessments can be held remotely. If you can hold the ETR evaluations remotely, then you can hold the ETR meeting during the time of the closure via telephonic or video conference means. If pieces of the evaluation cannot be conducted because school is closed, the evaluation would need to be delayed and a prior written notice for the same should be sent. If you have not yet conducted the evaluation and assessments, another option to consider is waiving the reevaluation and delaying it until return to the in-person education with parental consent or to conduct a records review. The guidance from the Ohio Department of Education indicates that all services should still be provided if parents consent to waive reevaluation.

Are we required to hold in-person meetings for ETRs and IEPs during a school closure?

If school closes, IEP teams are not required to meet in person. However, according to the Guidance, schools must continue working with parents and students with disabilities, to develop required documents – ETRs, IEPs, 504s, etc. If a plan or evaluation for a student expires during the time of school closure due to COVID-19, IEP/504 teams should offer to meet via telephone conference or videoconference with the parents. School personnel should attempt to determine the specific services that can be provided during the ordered school-building closure period. If the parent does not agree with meeting via telephone or video conference, then the meeting should be delayed until school reopens according to the Guidance.

What about evaluations and plans developed under Section 504?

The same principles apply as discussed above for ETRs and IEPs to those activities conducted by schools for a student with a disability under Section 504 according to the Guidance. You will want to review your school district’s 504 polices to determine 504 plan review and reevaluation timelines, as there is no requirement in federal law for how often must occur.

How do we help our staff in planning for this potential?

School district personnel should look at their evaluation and IEP timelines to determine which items may expire during the next few weeks/months of the 2019/2020 school year. It would be prudent to plan how items may be advanced or to begin discussions now with parents on what the plan will be in the event of a school closure.

by Jeremy Neff | Mar 12, 2020 | COVID-19 (Coronavirus), General, Special Education, Student Education and Discipline

UPDATE (3/12/20 at 6:20 PM): At 6 PM on March 12 the US Department of Education released new guidance on special education and COVID-19 that is available here.

In the past 48 hours it seems as if the already rapidly developing story of COVID-19, or novel coronavirus, has accelerated even more. With major spectator events being postponed, universities and colleges moving to online instruction, escalating infection rates around the globe, and the declaration of a pandemic by the WHO it seems inevitable that at least some Ohio public school districts will experience extended closures. These closures will raise important questions both in terms of employment and education. Given the unique and unprecedented challenges involved, we encourage you to work with legal counsel in real time to ensure effective and compliant responses.

What flexibility can we expect in meeting federal

requirements for education?

We can look to official guidance issued during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic to get a sense of what we might expect with COVID-19. On December 1, 2009, the US Department of Education (ED) issued a memo titled “Guidance on Flexibility and Waivers for SEAs, LEAs, Postsecondary Institutions, on other Grantee and Program Participants in Responding to Pandemic Influenza H1N1 Virus” (“SEA” refers to State Education Agencies like ODE, and “LEA” refers to Local Education Agencies like individual school districts). The guidance document discussed in generalities the willingness of the US Department of Education to offer flexibility regarding the requirements of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (now referred to as ESSA). It is reasonable to assume that flexibility will likewise be offered as COVID-19 has begun to force school closures. We will continue to update clients as specific guidance is issued.

Specifically regarding students on IEPs and 504 plans,

what services must we provide during a closure?

We are receiving many calls related to the delivery of

instruction during possible closures, and specifically regarding the delivery

of instruction to students with IEPs and 504 Plans. Here is what ED said on

this topic in 2009 regarding H1N1:

Must an LEA continue to provide FAPE to students with

disabilities during a school closure caused by an H1N1

outbreak?

The IDEA, Section 504, and the ADA do not specifically

address a situation in which elementary and secondary schools would be closed

for an extended period of time because of exceptional circumstances; however,

LEAs must be sure not to discriminate on the basis of disability when providing

educational services.

If an LEA closes its schools because of an outbreak of H1N1 that disrupts the functioning or delivery of educational

services, and does not provide any educational services to the general student

population, then an LEA would not be required to provide services to students

with disabilities during that same period of time. Once school resumes,

however, a subsequent individualized determination is required to decide

whether a student with a disability requires compensatory education to make up

for any skills that may have been lost because of the school closure or because

the student did not receive an educational benefit.

If an LEA continues to provide educational opportunities

to the general student population, then it must ensure that students with

disabilities also have equal access to the same opportunities and to the

provision of FAPE, where appropriate. SEAs and LEAs must ensure that, to the

greatest extent possible, each student with a disability receives the special

education and related services identified in the student’s individualized

education program (IEP) developed under IDEA, or a plan developed under Section

504.

There is no guarantee that ED would issue the same guidance

today for COVID-19, but given the parallels between the concerns in 2009 and

those today, this 2009 guidance is a reasonable starting point for planning a

compliant response to a potential school closure for COVID-19.

What are the special education implications of providing

online instruction during a closure?

It is notable that the approach that creates the most risk

for a school district, per the 2009 ED guidance, is to offer online instruction

during a closure. The reason this can become a problem is that students with

disabilities will need to be offered accessible instruction that meets their

unique needs. It is difficult to imagine how a district might provide “regular

prompting,” a common accommodation, to a child who is sitting alone at a

computer. And what of the child who does not have a computer or internet

access? Per the 2009 ED guidance it would be more legally compliant to not

offer any instruction at all than to offer online instruction without an

adequate plan for students with special needs.

This does not mean that online instruction should be ruled out. It just means that if online instruction is used there will need to be a plan for how this will serve students with disabilities. You should also consider the possibility of not immediately implementing online instruction. Given the mild winter and the fact that most schools significantly exceed minimum hours of instruction on their regular calendars, it is likely that a few days of closure (without online instruction) will not violate state minimum hours law. Even if a closure is longer lasting, pausing before implementing online instruction could provide important breathing room for student services to plan for serving students with disabilities.

Will we be required to provide compensatory education to

students on IEPs and 504 plans following a closure?

The 2009 ED guidance points to the fact that a discussion of

whether compensatory education may be required should follow any period of

closure regardless of what services are provided. Unless a child is already

assigned to home instruction at the time of the closure, any set of services

during a closure will in some ways not be in compliance with the child’s IEP.

While proactive amendments to account for anticipated closures could minimize

the risks, it would be ambitious for most districts to secure consent for

amendments for all IEPs. A more realistic approach could involve identifying

students who are most at risk of significant regression during a closure, and

working with parents to develop a plan to minimize that regression. Not only is

this educationally sound, it would be an important part of any legal defense

related to IDEA or Section 504 complaints. Once school resumes after a closure

you can revisit whether other compensatory services are appropriate.

Please continue to follow the Ennis Britton blog for updates

on COVID-19, and do not hesitate to call any of our attorneys with questions or

concerns.

by Hollie Reedy | Dec 20, 2019 | Special Education

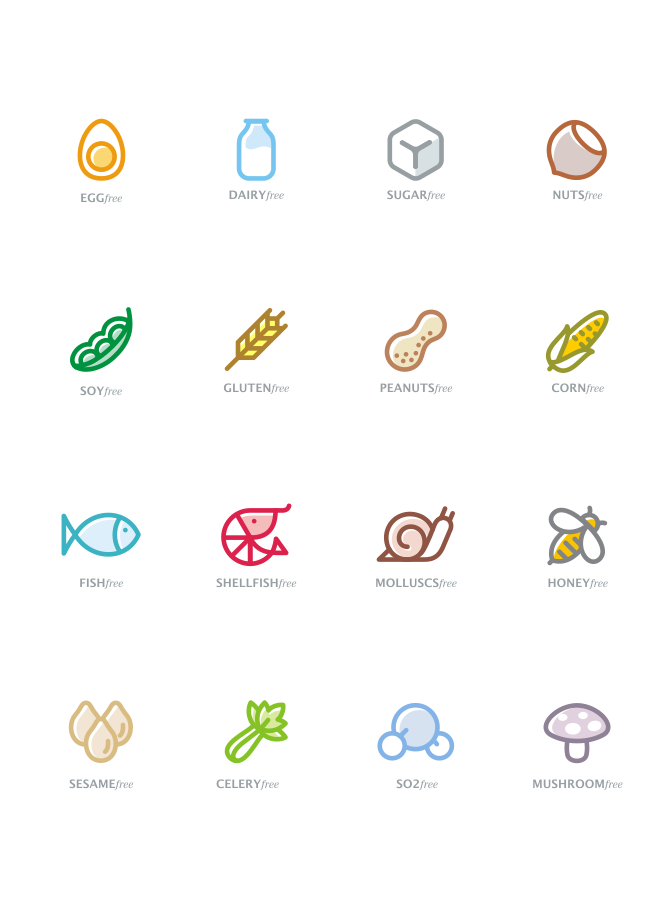

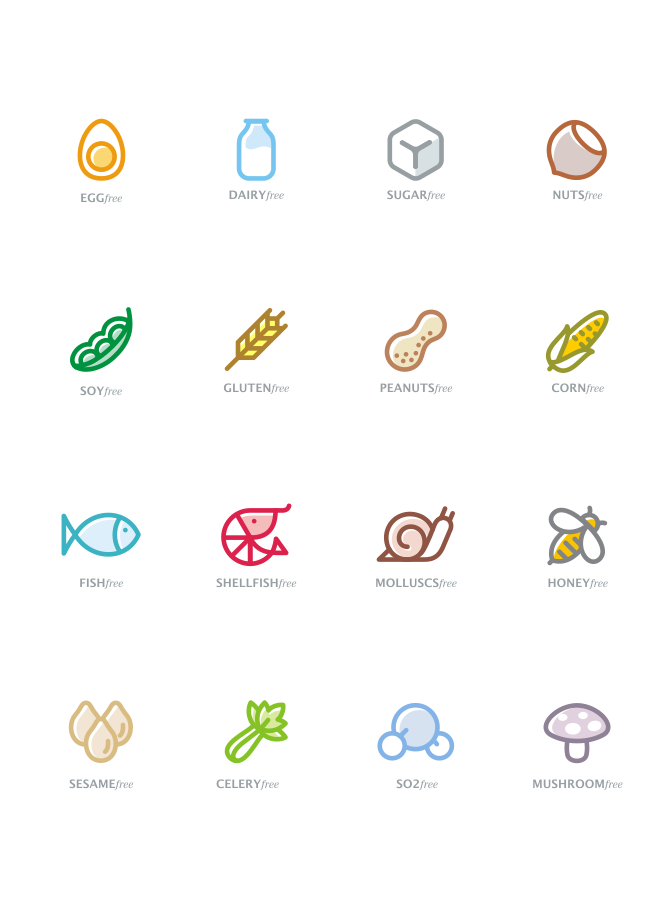

If it seems like there are more food allergies today, there are. Today, about 8% of all children have food allergies, an increase of 50% in ten years. This translates into 1 in 13 children, or about 2 per classroom. Individualized plans for the safety of each student with an allergy should be made to avoid exposure and reactions.

Students with food allergies may be eligible for special education supports and protections. For instance, a student could be IDEA- eligible as “other health impaired” if the allergies adversely affect learning or the student needs special education/related services due to the allergies. More commonly, students with food allergies may be eligible for a 504 plan if they have a physical impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. In the case of allergies, this could include breathing, immune system function, respiratory function, or learning. Districts may not discriminate against a student with a disability or deny them participation in school programs or activities. Schools IEP and 504 teams should discuss how allergies will be handled for students according to their particular allergy and its severity.

Individualized plans for the safety of each student should be developed to avoid exposure and reactions. The chosen accommodations must be implemented during all aspects of the school district’s activities and operations.

To determine if a student is eligible under 504 for a food allergy, district must screen out the use of medications or other measures to control the allergy. It is important to note that schools do not have to provide a risk-free environment, only a reasonably safe environment.

It is probably not surprising to you that the issue of accommodation of children with food allergies in schools has been the subject of special education hearings and litigation. Districts sometimes have to contend with diverse perspectives and demands, which they must reconcile on a daily basis. Here is a short summary of some 504 cases that may sound familiar to you.

In one case, a high school denied a student participation in a culinary arts program due to concerns about the student’s severe allergies to peanuts, dairy, egg, kiwi and crab. The student did not have a 504 plan at the time, but did have an emergency health plan to address exposure and response to a reaction. The student’s allergist had filed a letter stating the student could participate as long as he did not eat any of the foods prepared with ingredients to which he was allergic, and that he wore gloves when handling peanuts. The District attempted to contact the allergist one time, and did not contact him after that prior to making the decision to exclude the student. The student filed a complaint with the Office for Civil Rights, alleging disability discrimination. OCR found that the district had treated the student as a student with a disability even though it had not qualified him as one by excluding him from the program. They went on to find that the district had violated Section 504 procedurally, as it did not make a decision about the student’s exclusion with persons knowledgeable about the issues. (Bethlehem (NY) Central Sch. Dist. Office for Civil Rights, Eastern Division, NY, 52 IDELR 169, 109 LRP 30964)

Another case dealt with a student on an IEP whose allergy to peanuts and tree nuts was a life-threatening, airborne allergy. Initially, the District agreed that the student should be educated at a smaller private school that put into place significant protocols and regulations to ensure the student’s safety. The District proposed in a new IEP to change his placement to a public school on the basis that the student could be safely accommodated. This student also had autism with communication deficits, such that he would be unable to communicate his physical distress if he were having an allergic reaction. The parents rejected the proposed IEP and filed for due process. In a detailed decision concerning the peanut-free accommodations provided by the private school and the proposed peanut-restricted accommodations of the public school, the hearing officer found that the proposed IEP met the requirements of the law, which require only a reasonably safe environment, and plans in the IEP to ensure the student’s safety were adequate to prevent exposure and deal with a reaction if it did occur. (In Re: Student with a Disability Kentucky State Educational Agency 1213-16, 114 LRP 19510)

Finally, there was the Michigan case of a mother who refused to comply with the peanut free school building to accommodate another child who had a life-threatening, airborne peanut allergy. She wrote to the school, stating “I will not be cooperating not participating in the School’s 504 plan to another student. My child and I are not subject to, nor bound by, the provisions of the Rehabilitation Act….to meet my child’s needs, I will provide my child with the proper nutrition in her school lunch that I, in my sole discretion, deem appropriate.”

She filed a lawsuit seeking to enjoin the district from implementing the school-wide ban on nut products and requested money damages. She also alleged that her rights to equal protection and due process under the state and federal constitution were violated, and her child experienced unlawful search and seizure because her lunches were checked and when peanut items were found, replaced with appropriate alternatives.

The court of appeals rejected all her claims, finding that she lacked standing to challenge the 504 plan, that the school district’s peanut-free school policy was rationally related to a legitimate government interest, defeating the equal protection and due process claims. As to the unlawful search and seizure, the court stated that the school only looked for and removed banned items based on the parent’s notice to the school that they would not comply with the reasonable restrictions. (61 IDELR 231)

Practical takeaways

The most common food allergies are peanut and tree nuts, shellfish, milk, eggs, fish, wheat and soy. Some allergies are very severe, such as students who could have a life-threatening reaction to airborne particles of peanuts.

There are good resources for school professionals on ensuring a reasonably safe environment for students who have these allergies, and developing plans and emergency plans to accommodate the allergy to prevent a reaction, and to deal with a reaction if it occurs. The Centers for Disease Control has some great resources all gathered on one page, at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/foodallergies/index.htm, including Food Allergy Guidelines FAQ and Voluntary Guidelines for Managing Allergies. Both of these resources and many others, including information for school nurses and more, may be found on the CDC page.

Food allergy management is increasingly a common issue. Staff training on preventing exposure, recognizing signs of a reaction, responding with medication or the use of an Epi-pen, including environmental management in terms of cleaning surfaces and other items used in instruction, transportation staff and substitute teacher/aide training are all aspects of food allergy management that require ongoing attention. School staff, including IEP and 504 teams, should discuss food allergies and take appropriate steps to ensure students with allergies are properly accommodated.

Parent, staff and community education is likewise an ongoing effort in the management of food allergies in schools, involving education on watching ingredients in school snacks, lunches and the cafeteria, providing ingredient lists, and more. If you have an IDEA or 504 plan issue involving a food allergy, the EB special education team can assist in ensuring your team’s compliance with procedural and substantive requirements.

“Food Allergen Icons” by Milos Radojevic is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0